When OK Kanmani was released last year, several articles and comments rightly highlighted a facet of Mani Ratnam’s brilliancy: he is the only tamil filmmaker who have made love stories for three generations (Mouna Ragam in 1986, Alaipayuthey in 2000, OK Kanmani in 2015). But, in my opinion, another strong theme impregnates his film work: indeed, Mani Ratnam is a filmmaker who questions family ties. Nayagan is a gangster movie with a hidden family drama within, as it also depicts the complex fatherhood of Velu Nayakar (Kamal Hassan), an orphan who became a self-made don in Mumbai; Agni Natchathiram is about the conflictual relationship between two half-brothers, Gautham (Prabhu) and Ashok (Karthik), who have the same father but two different mothers; Anjali shows the struggle of a disabled child’s parents, Shekar (Raghuvaran) and Chitra (Revathi). It’s, especially, the mother-child relationship which seems to fascinate the filmmaker, as we can see in two of his most powerful movies: Thalapathi (1991) and Kannathil Muthamittal (2002). These two chefs d’oeuvre are rooted in a broken mother-child relationship: actually, the child abandonment is a founding act in these movies and Mani Ratnam has conscientiously frozen this moment in two beautiful frames that seem like genetically linked.

Nota bene : the analysis of these frames will also be a guise for some thoughts on the parent/child relationship in both movies, and above all, for me, an opportunity to show how strongly Mani Ratnam builds the “architecture” of his films, how subtly and intelligently he creates and gives life to his characters, how his visual language is itself enough to tell things without words. In short, it’s a way to express my fascination for his filmmaking.

Thalapathi and Kannathil muthamittal : two powerful stories about abandoned children.

It’s a known fact that Thalapathi, released in 1991, is one of Mani Ratnam’s mythological films, just like Roja or Raavanan. It’s an adaptation of one of the episodes of the Hindu epic, The Mahabharatha, involving Karna, Duryodhana, Arjuna and Kunti who respectively become Surya (Rajinikanth), Devaraj (Mammootty), Arjun (Aravind Swamy) and Kalyani (SriVidya) in the movie. But, actually, Thalapathi’s rich structure is like a Russian doll, with many layers: inside the mythological story, there is a gangster movie, which itself hides the emotional drama of Surya, an abandoned child, adopted and raised in a slum by an old loving adoptive mother. Surya finds a best friend and the family he never had in Devaraj, the local gangster, to whom he becomes the right-hand man, the « thalapathi ». Then, Devaraj and Surya stand up against the new district collector, Arjun, who has the mission to rid the town of gangs. As it is, the story seems to be “a man’s world” but just like James Brown sang it, “it would be nothing, nothing, without a woman or a girl”. Indeed, in Thalapathi, women characters are those who give an emotional dimension to the gangster story. In fact, Surya’s life path is successively marked by loved women who abandon him at some point: first, he was abandoned at birth by Kalyani, his biological mother and then, Subhalakshmi (Shobana), his lover, forced by her father, finally marries Arjun, the district collector, who happens to be Surya’s half-brother, as they have the same mother, that is to say, Kalyani…

Eleven years later, in 2002, Mani Ratnam directs, Kannathil Muthamittal, another movie rooted in an abandonment story. Indeed, Amudha (Keerthana) is abandoned by Shyaama (Nandita Das), a Sri Lankan refugee, then adopted and raised by a strong and loving couple, Thiruchelvan (Madhavan), a writer/engineer, and Indira (Simran), a television newsreader. Enjoying a happy life in Chennai with her parents, her two brothers and her grandfather, Amudha suddenly learns, on her ninth birthday, that she wasn’t born to Thiruchelvan and Indira. The truth has a bomb effect on Amudha, but, being a smart and determined kid, she cannot help wanting to meet her biological mother. Her repeated fugues convince her parents to take her to Sri Lanka. That’s why the second part of the movie depicts this quest for Amudha’s origins. The inspiration of this movie came through an article in The Times about an adopted child, raised in the US but taken back to the Philippines by her parents, to see her birth mother. Yet, Kannathil Muthamittal goes beyond this simple outline: indeed, as Mani Ratnam says himself, Amudha’s story is « the vehicle through which you travel through that conflict », that is to say, the Sri Lankan civil war and the resulting humanitarian crisis. The movie interweaves the inner drama of this abandoned child who is traveling towards her roots and the historical drama of the Sri Lankan people, who, conversely, has to exile and break away from its roots. Thus, Kannathil Muthamittal subtly draws a parallel between, the mother, Amudha longs for, and the motherland, Sri Lankan refugees yearn for.

Two frames for a founding act: the moment the mother abandons her child

This frame appears in the legendary introduction sequence of Thalapathi that any Mani Ratnam fan knows by heart. It begins, in 1959, with a black silent frame suddenly disturbed by the dawn’s singing birds and a festive music. While people are celebrating Bhogi, by burning their old and unwanted things and by dancing around a bonfire, a cart slowly moves in the distant background, carrying a lonely pregnant girl who is about to give birth. Then, with a travelling shot, Mani Ratnam shows peaceful woods in the morning light, only suggesting the delivery with the painful cries of the young Kalyani. Except the cart bull, nobody pays attention to the newborn’s first cry: his fate seems to be sealed, Surya will feel this loneliness his whole life.

Exhausted and desperate, the young girl decides to abandon her child in a wagon filled with rice bags and straw. To protect the baby, she swaddles him in a yellow blanket, the only legacy she leaves him, that will reunite them, at the end. Then, Kalyani says a few words, choked in sobs and desperate kisses to her child, and returns to her cart. But when the train starts, the wagon’s door suddenly opens and awakens a guilty maternal feeling in the young girl, who fears for her child’s life. She cannot help running after the train. That’s when this beautiful frame freezes the tragic separation, which contains all the elements of Surya and Kalyani’s destiny.

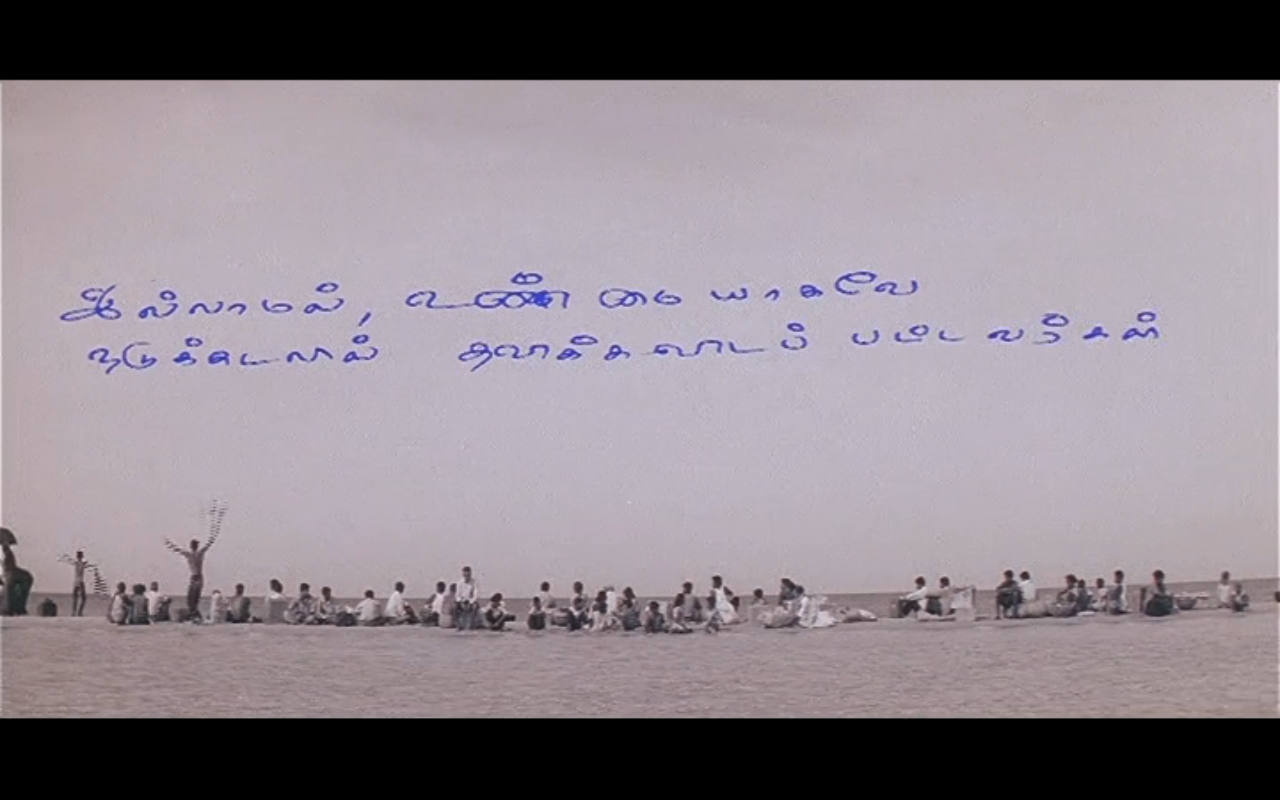

Just like Thalapathi,Kannathil Muthamittal starts by a peaceful dawn, but in Mankulam, a Sri Lankan little town. After the cheerful wedding of Shyaama (Nandita Das) and Dileepan (Chakravarthy), things go wrong and the civil war affects the newly married couple’s happiness. During a military operation, the innocent Shyaama loses her husband, who is a Tamil Eelam soldier: in a way, we should say that it’s the first act of abandonment in the movie, as Dileepan asks her to go. Then, the civil war is getting worse and the pregnant Shyaama is forced to exile to Tamil Nadu, and more precisely, to Rameswaram, where she gives birth to a baby girl. As in Thalapathi, the birth of the child marks the birth of the movie, but, however, in this introduction sequence, the abandonment act is only suggested but not shown. In fact, the past sequence is fragmented and scattered in the screenplay, just like a puzzle, or we should say, just like the abandoned child’s broken identity. After the Mankulam sequence, the past resurfaces later in the movie.

Indeed, during a family dinner scene shown with a beautiful circular travelling shot, Amudha strafes her parents with questions: “Yen poyutanga? Peyar enna? Yen enna thathu eduthinga?” (“why did she leave me?”, “her name?”, “why did you adopt me?” etc). That’s when Thiruchelvan decides to tell her the story behind her adoption, opening a flashback sequence that takes us back in the past, in Rameswaram.

This sequence starts with a beautiful intermingling between the Sri Lankan refugees images and Thiruchelvan’s voice-over, reading his own words, as the writer’s first book is inspired by a child born in Rameswaram’s refugee camp, that is to say, about Amudha. As Thiruchelvan tells Shyaama’s story, but from his own point of view, the same images from the introduction sequence, are here shown in black and white.

Shyaama becomes an anonymous refugee mother, but also a speechless character in Thiruchelvan’s story thanks to a beautiful zooming out crossfade shot. The reality becomes a fiction, the real mother is frozen as a drawing in Thiruchelvan’s novel. And in this flashback sequence, the moment of abandonment is finally shown, when Shyaama looks and touches her child one last time.

This frame seems to be genetically linked to the Thalapathi’s frame, and in fact, both frames have lot in common…

-

Black and white origins.

In both frames, the choice of black and white appears as an evidence to depict the past, and especially the founding act of abandonment. Though in Kannathil Muthamittal, most of the past sequences are in colours, black and white is used only for the few first minutes of the flashback where the intimate story of the child abandonment emerges from the collective story of Sri Lankan refugees. In both movies, black and white is a way to isolate this sequence from the rest of the movie, as if it was the seed from which the story was born, the root of which Surya and Amudha were torn, explaining the silent pain they will carry in them later. Mani Ratnam is very clear about it when he talks about Thalapathi: “Black and white gives the sense of this being a prologue without us having to define it as a prologue”. (…) These seven to eight minutes of build up lead to this particular moment, which should reveal what everything so far has resulted in.”.

-

The lonely abandoned child, came by the water.

In both cases, the newborn child is framed with a flat angle close-up shot, in the foreground while the mother appears in the background as if Mani Ratnam wants to warn us: the movie will follow the child’s point of view rather than the mothers. The baby is naked, fragile and alone in the darker side of frame, with nothing else than a thin blanket to protect him/her against the world. As Surya would say later to his mother, “Amma, naan porandhapove, sethurkka vendiyevan” (Mom,I could have died when I was born).

As I said, Thalapathi is a mythological film because of the Mahabharatha inspiration. But it’s quite possible that Mani Ratnam has used another kind of mythology, the Hebrew bible, to sketch Surya’s destiny. Indeed, in this train frame (and the whole introduction sequence), baby Surya is laying in a cradle made of straw, found by a bunch of poor kids, and then left in a little river that leads the baby to the slum where he is adopted and where he will end up spending the rest of his life. As it is, Surya’s genesis has a lot in common with the Hebrew prophet, Moses, genesis. In the Old Testament, it’s said that baby Moses, born in Egypt, is first hidden and then abandoned by his mother Jochebed, in a wicker basket by the Nile river. Then, he is found and adopted by none other than the Pharaoh’s daughter, who raises him as a member of Egyptian royal family. As we can read in Conversations with Mani Ratnam, by Baradwaj Rangan, Mani Ratnam’s team has worked a lot to keep the image of a river in the introduction sequence: “we tried to make the train take a curved route, almost like a river. We had to search a lot in order to find a railway path that gave the feeling of the child being carried along in the water.” As a matter of fact, the etymological meaning of Moses, “drew out of water”, could perfectly match Surya too…

In Kannathil Muthamittal, as well, the child arrives to his adoption place by the water element, as the pregnant Shyaama reaches Rameswaram in a raft full of refugees braving the stormy Indian Ocean. Thus, for both children, water element, whether it’s a river or the ocean, is a symbol of their origin, of their birth mother, maybe as a reminiscence of the amniotic fluid.

-

The disappearing mother, framed and imprisoned in a tragic destiny.

In both frames, Kalyani and Shyaama, the biological abandoning mothers are blurred and relegated in the background. Contrary to their child, they are in the brighter side of the frame, but slowly becoming a distant silhouette and disappearing from the frame just as from their child’s life.

In world cinema history just as in indian cinema history, child abandonment is a classic theme.

In both frames, Mani Ratnam has chosen to show a precise moment, when the mother, after abandoning her child, turns back one last time on him/her as if she suddenly regretted her act. In Thalapathi, the young Kalyani vainly and desperately runs after the train, after this child who is going to haunt the rest of her life. After the painful tearing of delivery, she undergoes another cruel and definitive separation. In Kannathil Muthamittal, Shyaama, in tears, comes back to touch her baby, through the window, one last time with her finger, as if to retain something of her child or, conversely, leave something of herself to the baby.

Above all, Mani Ratnam uses a beautiful frame within a frame technique to show that, by her act of abandonment, the mother condemns herself, she is imprisoned in a tragic destiny. In Thalapathi, the imprisonment feeling is reinforced by a succession of frames within frames on the young Kalyani. In Kannathil Muthamittal, the imprisonment seems even more obvious as Shyaama is framed in a barred window, as if she was locked in a prison cell. The frame within a frame is a classic visual technique which also enhances the feeling that the character is being observed, and that, we, the audience, are the observers.

A troubling fact is that Mani Ratnam used this barred window framing eleven years earlier, in Thalapathi, for another mother character imprisoned in her destiny. Indeed, Padma, the widow of Ramana, Devaraj’s henchman, is a tormented young mother. After giving birth to a little girl, she is visited by Devaraj and Surya, who happens to be the one who killed her husband. In this scene, the director uses a shot/reverseshot on Padma and Surya, looking at each other: the sad look of the widowed mother being the cause of the full of guilt look of Surya : being an abandoned child, he knows too well how painful is the feeling of an absent parent.

Also, using the frame within a frame to depict women characters imprisoned in difficulties (especially, family pressure symbolized by “domestic” frames), seems to be a common technique in Mani Ratnam’s filmmaking style. For instance, in Anjali, Chitra (Revathi), the mother condemned to see her child slowly leaving life; in Alaipayuthey, the secretly married Shakthi (Shalini) forced by her mother to dress up for an arranged marriage meeting; the same situation for Divya (Revathi) in Mouna Ragam ; in Iruvar, Ramani (Gauthami), the actress, mistreated by her violent uncle ; in Bombay, Shaila Banu (Manisha Koirala), the muslim girl, fearing to read a letter from her hindu lover. And so many others.

In both abandonment sequences, although the mother has not the opportunity to explain her act, she is not shown as an unfit mother and the abandonment seems understandable by the circumstances. In Thalapathi, Kalyani is an underage mother who is not responsible of her pregnancy, as Arjun’s father (Jayashankar) explains it to Surya : “nadanthathu aval thapu illa, yaaro senja paavam” (it’s not her fault, but someone else’s sin). In Kannathil Muthamittal, Shyaama, taking sand in her hand, tells her husband that she loves the land of Sri Lanka more than anything else, which explains that she goes back to her motherland to fight in the civil war. Yet, reasons remain unclear and questions of writer Thiruchelvan about Shyaama’s act of abandonment resonate in the viewer’s mind: “Sondha naattil avalukku enna irppu? Kadamaiyaa? Kanavanaa? Yuthamaa? Yaarukku theriyum” (What is waiting for her in her motherland ? Duty ? Husband ? War ? Who knows.).

The echoes of abandonment in Thalapathi and Kannathil Muthamittal.

-

From abandonment to adoption

In Kannathil Muthamittal, Mani Ratnam’s visual language is enough to show the handover between the biological mother and the adoptive parents.

For instance, the abandonment frame is immediately followed by a beautiful special effect, a zooming out crossfade that transforms the real image into a drawing illustrating Thiruchelvan’s novel that Indira, the future adoptive mother is reading. This sequence, an absolute visual delight, is another proof of Mani Ratnam’s brilliant filmmaking. Indeed, there is an intermingling between reality and fiction as Thiruchelvan’s novel is inspired by Rameswaram refugee camp, but it’s also a kind of handover between Shyaama, the biological mother and Indira, the adoptive mother. Shyaama abandons her child and becomes a fictional character, while Indira, by reading Thiruchelvan’s fiction, feels a motherly love for this child: the first one looses her motherhood while the second one feels the birth of her motherhood. As a matter of fact, Indira tells Amudha: “Adha padicha odana, Amudha’va pudichipochu, andha kadhaiyai ezhudiyavaraiyum pudichupochu”(Reading it, I instantly loved Amudha, and also the writer). In the climax, the link between Indira and Shyaama is visually shown: Indira telling Shyaama, “Ippo thukkikalame” (now you can hold your child). In the same way, Thiruchelvan tells Amudha that she made him write for the first time, that she brought his wife Indira to him, as this extraordinary couple decided to marry in order to adopt Amudha : that’s not the marriage that explains the child, but the child that explains the marriage. Here is a beautiful thought: Mani Ratnam shows, in a very sensitive way, that, in the adoption mind process, it’s not the parents who give birth to the child, but conversely, the child who gives birth to newborn parents. “Naanga unnai thathu edhukkala, neethan engalai thathu edutha” (we didn’t adopt you, you adopted us”), says Thiruchelvan.

The visual handover between biological mother and adoptive parents is also explained by the fact that, just as the abandonment seems to be the origin of the story, the abandonment frame seems to be the matrix of most of the parent/child frames.

For instance, the scene where Thiruchelvan/Indira meet baby Amudha in the orphanage owes a lot to the abandonment frame. Mani Ratnam uses a high-angle shot coming towards the baby imitating the view of couple and the audience’s, as well, who can face the baby for the first time in a bright daylight. Then, Shyaama’s only act of love to Amudha, the finger touch, is also the first act of love between Indira and the baby. As if the umbilical cord was extending from the biological mother to the adoptive mother, through this finger touch, as if both women were virtually passing on the baton of motherhood.

In the same way, when Thiruchelvan, being a single male, understands that he cannot adopt the baby alone, the frame shows the baby in the foreground, (in a barred cradle that reminds the barred window of the orphanage), and Thiruchelvan, blurred and relegated in the background, just like Shyaama in the abandonment frame. Just like her, he could lose Amudha at this moment.

Moreover, when Amudha runs away to Rameswaram, in the same orphanage where she was abandoned and adopted, traces of the abandonment frame obvious. In fact, the adoptive parents are looking at Amudha through the window, just like Shyaama did in the abandonment frame, except that they are “in” the orphanage trying to find a running away Amudha whereas Shyaama, being the one who ran away, was going “out” from the orphanage. There is a kind of inverse symmetry between the adoptive parents and the biological mother.

Contrary to Thalapathi which focuses on the abandoned child, Kannathil Muthamittal is also a story about the adoptive side. Mani Ratnam shows, in several scenes, the image of a loving and united adoptive family. It’s not astonishing that the tentative title was “Kudai”/The Umbrella. As Mani Ratnam says: « It was a concept that conveyed a sense of shelter, a family or a country. Adopted kids, adopted land, adopted immigrant, all become a part of it under a common roof, one common sky. The umbrella kind of represents various people under one cover.” And as matter of fact, it’s depicted in the last meaningful frame of Kannathil Muthamittal.

Conversely, Thalapathi doesn’t concentrate on the old adoptive mother who saved Surya from the river and raised him in the slum. Called “aatha”, “thai”, or “maharaasi”, by Surya, she remains very passive in the movie, though she is the one who comforts him, who listens to his anger, who is concerned about his gangster life. However, in some shots, Mani Ratnam shows the slum itself, with kids everywhere and caring people, as a protective and warm place, an umbrella, a shelter for Surya. We can especially see it when Devaraj comes to the slum, asking Surya to live with him, or when Surya and Padma, newly married, go back to Surya’s house.

At last, whereas the adoptive family commits itself with one child, the biological mother, in both movies, is shown carrying about dozen of other children (Tamil Eelam young soldiers for Shyaama, those of the charity medical camp for Kalyani), maybe to assuage her guilt or spread the love she could not give her own child. Kalyani says: “Mathavanga kozhandaya paathukkutta, yen kuzhandhaya yaaravadhu paathupaanganu oru nambikkai” (If I take care of other’s child, I hope someone would take care of my own child) while Shyaama first refuses to see Amudha, saying she already has 200 children.

-

Surya and Amudha: the mirroring destinies of two opposite abandoned children

Being two abandoned children, Amudha and Surya are, however, two opposite characters.

Until her ninth birthday, Amudha, a talkative and naughty girl, thought she was the biological daughter of a “writer, engineer and short-tempered” father and the “best Amma in the world”. In her first appearance in the movie, she is facing the camera, presenting herself and each member of her family. This reflects how much, at that point, her family is her identity, her family is her world. When Thiruchelvan wants to tell her the truth, she is running around him, just like the hindu divinity Ganesha, who, when he is asked to circle the world three times, walks three times around his parents, Shiva and Parvathy, saying that they were the whole world to him. But Amudha’s world collapses when the truth resurfaces, she is devastated by the news like a tempest. Conversely, Surya has always known that he had been abandoned: he has always lived with this tempest in him. When policemen ask him his identity by demanding his father and mother names, he hits them or yells that he doesn’t know. He is more introverted and intense than Amudha, just like a volcano about to erupt.

Both children’s names, given by their adoptive parents, reflect their two opposite personalities and explain how they are depicted in the movie (beautifully, we should say, by cinematographers Santhosh Sivan for Thalapathi and Ravi K.Chandran for Kannathil Muthamittal)

In Thalapathi, rather than using words, Mani Ratnam visually shows that the adoptive mother names the baby Surya, by a beautiful crossfade from the black and white sequence to the color sequence. It’s a new beginning for the movie, a new birth for the adopted baby. This name is no coincidence: Surya is the sun, Surya is the fire, who threatens and burns his enemies just like the Bhogi bonfire. That’s why he warns the district collector, Arjun in a famous scene: “Surya sir, orasadhinga”. That’s also why he burns alive the man who tried to kill his best friend, Devaraj. From there, the whole movie is impregnated by sunlight and by a yellowish orange colour.

In Kannathil Muthamittal, the baby is named Amudha by her mother Indira. She is inspired by the last sentence of Thiruchelvan’s novel, “Kudai” : “Avaladu azhugai, amudhamaaga ollithathu” (her first cry flowed like nectar). Here again, I don’t think the name was randomly chosen by Mani Ratnam : Amudha is the tamil translation of Sanskrit word “Amrutham” that is the nectar of immortality, result of the churning of the Ocean of milk by the mythological Devas and Asuras. And indeed, in a way, our Amudha, is sweet like this nectar of immortality and her birth mother came to Rameswaram, through a stormy Indian ocean. Thus, Amudha is frequently associated with ocean or water, blue or light green. The beach or seaside scenes are crucial turning points in Amudha’s life. Each abandoned child has his natural element (fire for Surya, water for Amudha), which become recurrent motifs in the movie.

However, despite all these differences, both characters come from a broken mother-child relationship, both suffer from a broken identity and a kind of loneliness and, therefore, they have similarities.

For instance, in both movies, the main theme songs use the same floral metaphor for the abandoned child. In Thalapathi : “Chinna thaayaval thantha raasave / Mullil thondriya chinna rosave” (A little prince given by a little mother / A little rose arisen from a thorn). In Kannathil Muthamittal : “Oru deivam thantha poove / Kannil thedal enna thaaye” (A flower given by a divinity / What is this quest in your eyes). Notably, in Thalapathi, the image of a flower arisen from a thorn could be a wanted reference to Mahendran’s Mullum Malarum. Mani Ratnam said that he wanted to find back in his Thalapathi’s Surya, the flayed Kali of Mullum Malarum, intensly performed by Rajinikanth. In both cases, the characters are, indeed, flayed by life, they can be harsh like the thorn and sweet like the flower: “chella mazhaiyum nee, chinna idiyum nee” (You are the tender rain / You are the little thunder). The song “Chinna Thaiyaaval” is the lullaby Surya never had and a theme of his loneliness, as Mani Ratnam himself says, it depicts “this image of Karna who is standing alone, brooding, and who is doomed to be a loner from birth, when he was abandoned (…) Chinna thaayaval was conceived more as a song for Rajini. It’s about his loneliness, his seeking the person he’s never met. So it was like a lullaby that was never sung”. In Kannathil muthamittal, the male and female version of “Oru deivam thantha poove” are sung from Thiruchelvan and Indira’s points of view, and they define a complex parent-child relationship, full of contradictions.

There are also similarities in the picturization of the two abandoned children. Indeed, as I said before, both have come from the water. The river for Surya and the Indian Ocean for Amudha are their only visible link with their origins, with their birth mother. And, as a matter of fact, both children are facing alone this river/ocean, when they are wondering why they were abandoned, where the absent mother could be. In both movies, adoptive parents then join them answering their painful questions.

Another common point is that both Surya and Amudha are subtly linked with their birth mothers through a visual motif which is like a symbolic visual umbilical cord.

In Thalapathi, the yellow blanket seems to be omnipresent in Surya’s life just as his thoughts about his mother. It’s the only legacy she left him and also the security blanket that reassures baby Surya but also the 32 years old Surya, still longing for his mother. In the scene where Kalyani understands that Surya is her abandoned son, the way she catches the yellow blanket and takes it back, shows how much the link between Surya and Kalyani has remain intact.

In Kannathil Muthamittal, the same barred window framing is used for Shyaama when she abandons the baby and for Amudha when she goes back to Rameswaram and gets disappointed of not finding her birth mother. Both are outside the orphanage, going towards Sri Lanka: in her quest of origins, Amudha follows the footsteps of her birth mother. An interesting fact is that, in Thalapathi, there is also a scene where Surya, behind a barred window, yells “Enna petha amma, nee enga irukka?” (Birth mother, where are you?), without much hope and above all, to mock his adoptive mother who is worrying about what his birth mother could think of his way of life.

To conclude this article, I have to say some words about the reunion of the child and the birth mother, a crucial moment. Each reunion scene is impregnated with the element associated to the abandoned child, fire/sun for Surya, water for Amudha: in Thalapathi, Kalyani appears in Surya’s house, surrounded by a beautiful orange sunlight whereas in Kannathil Muthamittal, the reunion is rainy.

Both Surya and Amudha have thousand of questions to ask their birth mother: Amudha has methodically written her 20 questions in her memory book whereas Surya kept these questions in him for 32 years. However, Amudha and Surya ask the same first question: “Yen ma enna vittuttu poyitta?” / “Neenga yen enna vittuttu poyuttinga?” (Why did you leave me?). However, in front of the birth mother, after a few questions, they are overwhelmed by emotions and they can hardly speak. Surya says: “Yennakavadu oru naal, unna pakkumpothu, aayiram kelvi kekkalam’nu ninaichirundhen. Aana ippo, unna pakkumpodhu, en kovam ellam poyudiruchu’ma” (I wanted to ask you thousand questions if could meet you one day. But now, seeing you, my anger has gone”). Amudha also, between tears and anger, couldn’t speak more.

In fact, both reunion scenes are marked by the mother character, collapsing in tears, as a relief of her pain. The two abandoned children, on their side, find relief when they can, at last, call their mother “Amma”. Surya says that he wants to call Kalyani “Amma”, without stopping whereas Amudha fulfills this wish, saying repetitively “Amma” to make Shyaama stay. In both movies, one character wants a happy ending where everybody is united, somewhere else : Kalyani in Thalapathi : « Yen kuda vanthuru, nammellam onna irukkelam » (Come with me, let’s all of us be reunited), Amudha in Kannathil Muthamittal : “Aama, ivangala namma kuda vara sollunga, Madras’ku kuttittu polam” (Mum, tell her to come with us, let’s take her to Madras).

However, contrary to Kannathil Muthamittal, in Thalapathi, Kalyani and Surya has already met several times before this reunion, without knowing the truth. And especially, after learning that collector’s mother is his mother too, Surya follows her in the temple: that’s the second version of “Chinna thaiyaval”.

In this song sequence, the first frames show the silhouette of Kalyani surrounded by a river bathed in sunlight, certainly the same river that led Surya to his adoption slum: at that point, Surya is still this boy contemplating the river to reach his birth mother, he can see that his mother is surrounded by the sunlight, by thought about Surya. The reunion scene confirms the symbiosis between the mother and the son, as the mother is surrounded by a rising sun. Thus, Thalapathi’s architecture seems to be based on inverse symmetry : for instance, Kalyani asks Surya to spare Arjun’s life, and, then, in the next scene, she asks Arjun to spare Surya’s life. But, there is also a kind of circularity in the movie. For instance, the adopted child, Surya, becomes himself an adoptive father for Padma’s daughter, Thamizhazhaghi. Whereas Amudha listens to the story of her abandonment, Surya is an abandoned child who becomes the parent who tells his own story to her adoptive child.

But above all, Surya’s story begins and ends in a train. In the last scene, Kalyani tells Arjun that, rather than go back with him, she will stay with Surya. She doesn’t give any explanation except a tender smile to this son she missed more than 32 years.

In Thalapathi but also in Kannathil Muthamittal, the climax is for the characters, the end of a chapter in their life and the beginning of another : a new birth.

Shakila Z.

References :

For all the quotes of Mani Ratnam : Baradwaj Rangan, Conversations with Mani Ratnam, Penguin Books, 2013.