‘Thenmozhi’ was one of last year’s hit songs and like many, I was hooked on, as much as I loved Thiruchitrambalam. The interesting thing when you are obsessed with a song is that you are not only enjoying it as an object of consumption but also questioning its multiple and meaningful dimensions. That’s how I understood that this song was not only a loveable hit song made by a trinity of artists in the spirit of their times (composed by Anirudh, written by Poet’u Dhanush, sung by Santhosh Narayanan), but that it might have a more pivotal importance in Dhanush filmography but also, in the evolving Tamil cinema.

The track is written as a “love failure” song that takes the form of an heart-broken man’s statement addressed to a beloved but non-reciprocating woman. In short, it could have been used at multiple places in Thiruchitrambalam, given the succession of disappointments in Thiru’s love life. Yet, it’s used specifically after Shobana’s rejection but in a shortened version matched with the song’s twin version, ‘Mayakkama Kalakkama’. Indeed, to match more precisely the screenplay, Dhanush had to write another version, focusing on Thiru’s tormented state of mind, and rooted in the legacy of Kannadasan’s ‘Mayakkama Kalakkama’.

(not a) soup song

Songs about the pain of love are plenty in the history of Tamil cinema but since the 2000s, a specific sub-category has emerged, with some leitmotiv elements tainted with misogyny : lyrics blaming women for breaking men’s hearts, song sequences staged in a public space, specifically in the streets or in a wine shop, a group of male friends supporting the heart-broken hero, rough expression of emotions with the help of alcohol and of some tough dance moves, as written by Premalatha Karupiah in her analysis of break-up songs. In short, nothing to diminish the hero’s gethu even at the deepest bottom of his heartbreak.

And, as a matter of fact, the genesis of soup songs in Tamil cinema is related to Dhanush, as an actor but also as a lyricist. In 2011, Dhanush and Selvaraghavan wrote ‘Kadhal en Kadhal’ for their film Mayakkam Enna, in which, aside from the problematical refrain “Adida avala, odhada avala, vettura avala”, we can also hear this line : “soup’la thenguren, nenjudhaan thangala”. The soup becoming a popular metaphor referring to the emotional state of men rejected by the women they want. Above all, the roaring success of ‘Why this Kolaveri’ in 2012 made this song, the matrix of an unstoppable and indigestible wave of soup songs pouring out in Tamil cinema during the 2010s.

Though ‘Thenmozhi’ is rooted in a soup song-friendly context, it doesn’t fall into this category. It couldn’t actually. Because of Thiruchitrambalam itself, because of Thiru and Shobana, because of the arc of evolution of Dhanush’s filmography, because of the mentality shifts in today’s Tamil cinema. Of course, the song begins like a typical soup song as it addresses the beloved woman to expose the pain suffered by the man she rejected but also his pride : “Onna nenachonnum urugala podi, sogathil onnum valakkala thadi”. But, despite this coloration, the song escapes the usual traits of soup songs.

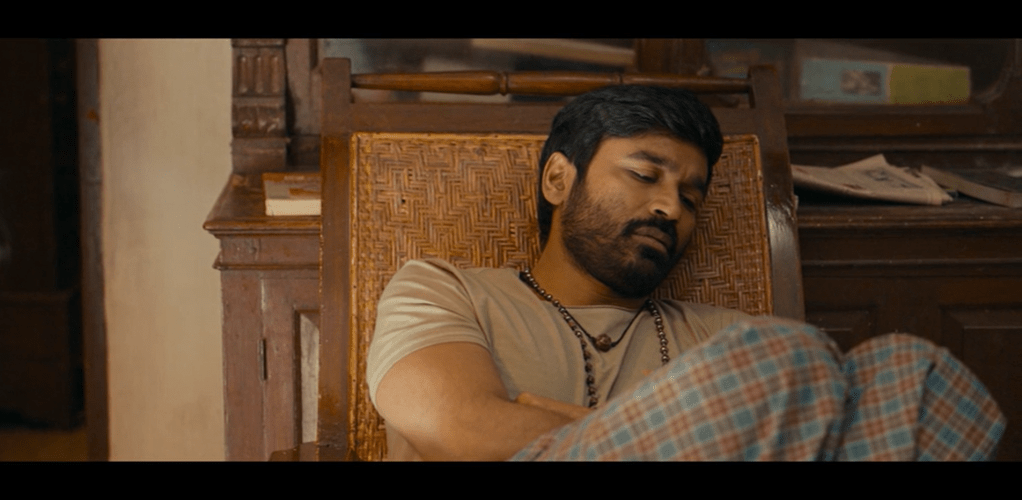

First, in the typical soup song, the beloved woman/all women are portrayed in a most misogynistic manner, compared to demons, headaches, poison, devaluated for their fakeness, for their white skin hiding a black heart (‘White skin’u girl’u, girl’u heart’u black’u’ in ‘Why this Kolaveri di’). In ‘Thenmozhi’, tender words of affection are pouring out : ‘Thenmozhi, poongodi (…) Vanmadhi, paingili’. Proving that even in the most unbearable pain of rejection, a ‘love failure’ song could remain a song of love. Secondly, in this song, there is no sign of hyper-masculinity or the necessity of maintaining the hero’s gethu : no groups of male friends but an omnipresent female best friend, no tough dance moves but a static and pensive hero, no solace found in alcohol but in Ilaiyaraaja songs.

A new vision of love

« Un mela kuttram illa, nee onnum naanum illa »

In ‘Thenmozhi’, the lyrics are not desperately trying to showcase the hero’s masculine pride but instead, they reveal the acceptance of his own vulnerability, a philosophical distance with a touch of self-derision : “Gethu kaattittu azhuvureney, azudhu mudichittu sirikkiraney”. This is exactly what makes Thiru’s character incompatible with the usual soup song. He is not the formula hero who clumsily displays his masculinity with a bunch of drunken friends to escape his feelings, he is the kind of hero who cries alone in his room, listening to some Raaja songs, to contemplate these same feelings.

Above all, while the typical soup songs use to project men’s desire on women, blaming them for being dangerous, insincere and destroying loves, two lines in ‘Thenmozhi’ break this misogynistic routine : “Un mela kuttram illa, nee onnum naanum illa”.

Even though it could also be Thiru’s shadow addressing himself, these lines are clearly a declaration to the beloved one, telling her that she is not guilty of anything because she is not him, that SHE is not responsible for HIS feelings. After years of women-blaming soup songs, these very simple lines appear like a breathe of fresh air, proving a new kind of maturity not only in the portrayal of women but above all, in the understanding of what love actually is. As if the lyricist had dug deeper to understand the complexity of love, as if Thiru, maybe because of his friendship with Shobana, understood that love is not about displaying power over someone but about accepting one’s own vulnerability. In short, as if Dhanush had met bell hooks :

“At least when you hold to the dynamics of power, you never have to fear the unknown; you know the rules of the power game. The practice of love offers no place of safety. We risk loss, hurt, pain. We risk being acted upon by forces outside of our control.” (bell hooks, All about love, new visions)

a redemption song ?

That being said, it’s quite interesting to consider the meta interpretation we could make of this song, as if Dhanush has written this song as a redemptory response to the soup songs he wrote ten years back. The “Un mela kuttram illai, nee onnum illai” lines especially resonate as a much needed correction after so many lines, in the past decade, portraying women as guilty of breaking men’s hearts. In these times of feminist-washing in so many hero-centric movies (compare Vijay dialogues about Asin’s sleeveless western clothes in Sivakasi and his monologue defending women’s rights to dress as they want in Master), I tend to think that there is a genuine growth in Dhanush, and consequently, in his writing about the pain of love, still in a male perspective but in empathy with the other side. I am quite sure (well, I am hoping) that ‘Thenmozhi’ is his way of saying that he is definitively closing the soup boy chapter of his filmography.

To many more anti-soup songs because « love failure » songs should actually be songs about love and not about hate, songs that, we, women and men, could sing loudly and happily, without any reluctance. Like the girls in this bus.

Shakila Zamboulingame

Leave a comment